The Round Robin topic for February: Description. What is your saturation point? What is not enough? How do you decide what to include and when to hold back to allow the reader to fill in the blanks? Do you ever skim description when reading a book? If so, what description are you most likely to skip?

Wow! This is an interesting topic and I can’t wait to read all these other authors’ take on the subject. It’s a hard question to answer, not just here for this Round Robin Blog, but every time I write a book.

Just the right amount of description puts you right there in the scene, feeling the soft breeze of a moonlit night on the beach or the damp chill of a winter rain, hearing the rattle of keys dropped on a glass topped table, or the startling rustle of something unexpected moving behind you, smelling the choking pall of heavy smoke, or the enticing whiff of man’s cologne. Details are important for setting the scene and the mood. They also give the reader their first mental image of a character. Well used, they tell more than a character’s physical appearance or beauty. A man might have the physique of someone who worked and played hard. Or a woman might be the kind that turns a man’s head, but demands a no-nonsense attitude. I like that kind of description because it tells me more about the character than the details of their physical appearance and allows me to flesh them out to suit my vision of how they should look. A good story needs descriptive narrative otherwise it would come across like a police report. Consider the difference between ‘He picked up the phone and called her.’ With ‘His hand hovered over the receiver. He really didn’t want to talk to her just now. He sighed and picked up the phone.’ Obviously a lot more words, but also a lot more information than just the simple action of calling someone on the phone. Description can be packed into dialog as well. As in “get your clammy hands off me.” or “What’s not to like? She’s soft in all the right places and very willing.” And in action: If he scrambled down the embankment and into the culvert soaking his shoes, you know he wasn’t walking casually and there was water in the culvert without it actually being said. But description can be overdone, as well.

Just the right amount of description puts you right there in the scene, feeling the soft breeze of a moonlit night on the beach or the damp chill of a winter rain, hearing the rattle of keys dropped on a glass topped table, or the startling rustle of something unexpected moving behind you, smelling the choking pall of heavy smoke, or the enticing whiff of man’s cologne. Details are important for setting the scene and the mood. They also give the reader their first mental image of a character. Well used, they tell more than a character’s physical appearance or beauty. A man might have the physique of someone who worked and played hard. Or a woman might be the kind that turns a man’s head, but demands a no-nonsense attitude. I like that kind of description because it tells me more about the character than the details of their physical appearance and allows me to flesh them out to suit my vision of how they should look. A good story needs descriptive narrative otherwise it would come across like a police report. Consider the difference between ‘He picked up the phone and called her.’ With ‘His hand hovered over the receiver. He really didn’t want to talk to her just now. He sighed and picked up the phone.’ Obviously a lot more words, but also a lot more information than just the simple action of calling someone on the phone. Description can be packed into dialog as well. As in “get your clammy hands off me.” or “What’s not to like? She’s soft in all the right places and very willing.” And in action: If he scrambled down the embankment and into the culvert soaking his shoes, you know he wasn’t walking casually and there was water in the culvert without it actually being said. But description can be overdone, as well.

Once upon a time, I read a lot of Regency Romance, but as much as I loved the era, I got tired of reading detailed descriptions of how the heroine was dressed. I had no need to know if the dress had three flounces around the hem, or an apron of creamy satin or what kind of lace graced the neckline. Nor did I want a detailed outline of the hero’s smallclothes and that he was a master at tying a waterfall cravat. Perhaps that’s a key component of that genre – if so, that’s probably why I’ve stopped reading them. And I confess to skipping descriptive narrative that’s either too much or seems irrelevant. Years ago, when Outlander first came out, I devoured the book, read it several times, including all the descriptive stuff. But with each succeeding book, Diana Gabaldon has gone into more elaborate detail about things that have no impact on the plot or the characters. By book three I was skipping whole sections of her endless detail. By book five I stopped reading them at all, and that’s saying something for a reader who fell completely in love with Jamie Fraser and couldn’t get enough at the start.

Once upon a time, I read a lot of Regency Romance, but as much as I loved the era, I got tired of reading detailed descriptions of how the heroine was dressed. I had no need to know if the dress had three flounces around the hem, or an apron of creamy satin or what kind of lace graced the neckline. Nor did I want a detailed outline of the hero’s smallclothes and that he was a master at tying a waterfall cravat. Perhaps that’s a key component of that genre – if so, that’s probably why I’ve stopped reading them. And I confess to skipping descriptive narrative that’s either too much or seems irrelevant. Years ago, when Outlander first came out, I devoured the book, read it several times, including all the descriptive stuff. But with each succeeding book, Diana Gabaldon has gone into more elaborate detail about things that have no impact on the plot or the characters. By book three I was skipping whole sections of her endless detail. By book five I stopped reading them at all, and that’s saying something for a reader who fell completely in love with Jamie Fraser and couldn’t get enough at the start.

I still enjoy romance – who doesn’t love a good love story! But today I read a far wider variety of genres, including action, adventure and stories with a patriotic or military theme. But even here, my eyes begin to glaze over when the author, either because they are in love with the paraphernalia, or because they’ve done a ton of research and just can’t bear to leave out any of the details they’ve so carefully researched. I want the story – the action – the characters either doing or surviving. I’d like to know they are adequately armed and have the latest in technology, that they are savvy about using the internet, or not, if they are well trained and physically fit, but I don’t need the minutiae. Consider Randy Wayne Wright’s Doc Ford series. We all know Ford was once a covert operator and now he’s a marine biologist, but Wright doesn’t bore me with detailed descriptions of the things Ford does in his lab or in endless backstory about his shadowy past. He just fills the pages with colorful characters, a setting that makes me want to go to Sanibel and tells an engaging story that draws the reader in.

I think there are some details the reader does need to know. It might be important that a man is wearing cargo shorts rather than a suit or a uniform. Adding that they are faded and frayed might say something else about the character or the situation. If a character is wearing all black, including a balaclava that also tells you something about what he might be up to. And a heroine with 4 inch heels and a briefcase paints a definite picture. If the hero is in a gunfight, knowing he’s only got a handgun with an 8 round magazine and the villain is armed with an AK-47 that definitely sets the scene and puts the reader on the edge of their seat. But do we have to read the sales brochure or the military procurement description of the gun to get that picture? Or know where the heroine shops? Likewise, if a detective is entering a building that might have clues, a hostage, or a bad guy, details like suspicious noises, loss of electric power, too many places to hide, or shadows sets a compelling scene, but you don’t have to be offered a detailed floor plan or a lengthy discussion on the reason for the power outage. So, like I said, it’s a balancing act. How much to include, how much to leave out?

I think there are some details the reader does need to know. It might be important that a man is wearing cargo shorts rather than a suit or a uniform. Adding that they are faded and frayed might say something else about the character or the situation. If a character is wearing all black, including a balaclava that also tells you something about what he might be up to. And a heroine with 4 inch heels and a briefcase paints a definite picture. If the hero is in a gunfight, knowing he’s only got a handgun with an 8 round magazine and the villain is armed with an AK-47 that definitely sets the scene and puts the reader on the edge of their seat. But do we have to read the sales brochure or the military procurement description of the gun to get that picture? Or know where the heroine shops? Likewise, if a detective is entering a building that might have clues, a hostage, or a bad guy, details like suspicious noises, loss of electric power, too many places to hide, or shadows sets a compelling scene, but you don’t have to be offered a detailed floor plan or a lengthy discussion on the reason for the power outage. So, like I said, it’s a balancing act. How much to include, how much to leave out?

As an author, I sometimes leave out important details. I might assume a general knowledge of things that the average person perhaps does not have. Or I know my character’s backstory so well and in my eagerness to get to the action, I forget there are details of that backstory the reader needs to know to understand the character’s motivation. My upcoming release, Iain’s Plaid, is set during the months leading up to the start of the Revolutionary War. I admit it’s one of my favorite periods in American History, and I know a lot more about it than most people do, but I’m still surprised to discover that the only thing from that moment in history that most people are aware of is the Boston Tea Party, or the vague notion that it was all about taxes. My editor, God bless her, pointed out to me all the places her lack of knowledge left her wondering why my hero was doing what he was doing. Or what was going on historically. I had to find ways to weave that knowledge into the story without it sounding like a history lesson.

As an author, I sometimes leave out important details. I might assume a general knowledge of things that the average person perhaps does not have. Or I know my character’s backstory so well and in my eagerness to get to the action, I forget there are details of that backstory the reader needs to know to understand the character’s motivation. My upcoming release, Iain’s Plaid, is set during the months leading up to the start of the Revolutionary War. I admit it’s one of my favorite periods in American History, and I know a lot more about it than most people do, but I’m still surprised to discover that the only thing from that moment in history that most people are aware of is the Boston Tea Party, or the vague notion that it was all about taxes. My editor, God bless her, pointed out to me all the places her lack of knowledge left her wondering why my hero was doing what he was doing. Or what was going on historically. I had to find ways to weave that knowledge into the story without it sounding like a history lesson.

Sometimes leaving out detailed description allows the reader to imagine the world in their own mind. Whatever things an individual reader might feel is heroic or compelling can be attributed to the hero or heroine of the story if they aren’t described in intimate detail, and the reader will be naturally partial to him or her just because of that very personal bias. There are some characteristics that are critical to the story, or the motivations behind the hero or heroine’s actions, but a lot of other stuff can be left to the readers’ imaginations. The same goes for the worlds they live in. Include the details that drive the story or impact the outcome, leave out the stuff that doesn’t influence the story or the characters in any meaningful way. Often those details are things the author likes but the story doesn’t really need.

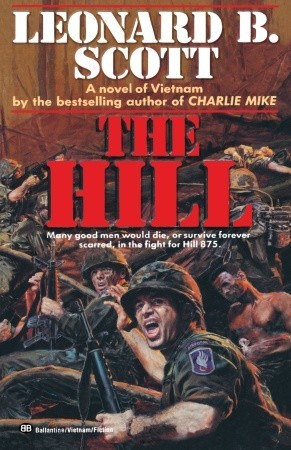

It also depends on what effect the author is going for. Leonard B. Scott wrote a book called The Hill. Set during the Vietnam War, his hero was a native American who had grown up loving the hills of his birth and Scott lets you into that love and respect before he drops the hero into the chaos of war and puts him on a hill that the US Army is determined to take regardless of the cost. But the added drama for that story was the Vietnamese general who loved the hill of his birthland. The very hill the Americans were determined to take. A hill the Viet Cong had riddled with tunnels and defenses. Seeing that battle from both points of view added a whole other layer of suspense and tragedy. The way that story was told let the reader into the hearts and souls of men from both sides of that bitter struggle and had a very different impact than had one only seen it from the American’s point of view. Sometimes an author wants the reader to be as surprised by the actions of the antagonist as the protagonist is, so you won’t know those details from the other side of the story. Personally, I think it adds to the suspense if you know something the protagonist doesn’t know, but the Perry Mason stories and the Sherlock Holmes mysteries are classic examples of the reader being as much in the dark as everyone else in the story other than Mason and Holmes until the final reveal. And those stories are classics.

It also depends on what effect the author is going for. Leonard B. Scott wrote a book called The Hill. Set during the Vietnam War, his hero was a native American who had grown up loving the hills of his birth and Scott lets you into that love and respect before he drops the hero into the chaos of war and puts him on a hill that the US Army is determined to take regardless of the cost. But the added drama for that story was the Vietnamese general who loved the hill of his birthland. The very hill the Americans were determined to take. A hill the Viet Cong had riddled with tunnels and defenses. Seeing that battle from both points of view added a whole other layer of suspense and tragedy. The way that story was told let the reader into the hearts and souls of men from both sides of that bitter struggle and had a very different impact than had one only seen it from the American’s point of view. Sometimes an author wants the reader to be as surprised by the actions of the antagonist as the protagonist is, so you won’t know those details from the other side of the story. Personally, I think it adds to the suspense if you know something the protagonist doesn’t know, but the Perry Mason stories and the Sherlock Holmes mysteries are classic examples of the reader being as much in the dark as everyone else in the story other than Mason and Holmes until the final reveal. And those stories are classics.

I guess the bottom line for authors is to understand the impact you want your story to have, then find skillful ways of including the details that must be there to create that effect, while avoiding info dump and long narrative passages of back story that the reader doesn’t need to know and might get bored with. One axiom of writing I’ve heard a lot regarding whose point of view to be in is, “who has the most to lose?” That’s because being inside the head of the character with the most to lose gives the reader a chance to know more details about the stakes. An author needs to keep that in mind when deciding what descriptive information to include and what to leave out. What are the stakes? If the reader doesn’t know this detail, will it change his expectations? Conversely, if this detail makes no difference to the outcome, why is it there in the first place? If Diana Gabaldon had asked herself that question and realized it was just her fascination with all that deep research that compelled her to include way too much detail and kept her books to 300 or 400 pages instead of a thousand, I might still be reading her books.

Which leads to my last observation for authors. KNOW YOUR READERS. Obviously given Gabaldon’s over the top success, most of her readers either love that kind of detail or are willing to bear with her. W.E.B. Griffin’s readers are similarly enthralled with his endless recital about arms, procedure, backstory and places. On the other side of the road are those who prefer the straight-forward Jack Reacher. It doesn’t get much simpler than carrying a toothbrush in his pocket and having no home or cell phone. Lee Child includes just enough detail about Jack so I knew the caliber of the man, his stature and military background, but the rest was up to my imagination as the plots unfolded, and when Tom Cruise was cast as Reacher for the movies, I was appalled. Arrogant, short and self-centered, Cruise couldn’t possibly live up to the larger-than-life man I had imbedded in my psyche. I probably would have been equally appalled if John Wayne had been cast as James Bond, but then, Ian Flemming had already endowed Bond with a fairly well fleshed out description.

Which leads to my last observation for authors. KNOW YOUR READERS. Obviously given Gabaldon’s over the top success, most of her readers either love that kind of detail or are willing to bear with her. W.E.B. Griffin’s readers are similarly enthralled with his endless recital about arms, procedure, backstory and places. On the other side of the road are those who prefer the straight-forward Jack Reacher. It doesn’t get much simpler than carrying a toothbrush in his pocket and having no home or cell phone. Lee Child includes just enough detail about Jack so I knew the caliber of the man, his stature and military background, but the rest was up to my imagination as the plots unfolded, and when Tom Cruise was cast as Reacher for the movies, I was appalled. Arrogant, short and self-centered, Cruise couldn’t possibly live up to the larger-than-life man I had imbedded in my psyche. I probably would have been equally appalled if John Wayne had been cast as James Bond, but then, Ian Flemming had already endowed Bond with a fairly well fleshed out description.

So, now that you’ve borne with my ramblings on the topic, hop on over and check out what these authors have to say on the subject.

Marci Baun http://www.marcibaun.com/blog/

Marci Baun http://www.marcibaun.com/blog/

Beverley Bateman http://beverleybateman.blogspot.ca/

Anne Stenhouse http://annestenhousenovelist.wordpress.com/

Dr. Bob Rich https://bobrich18.wordpress.com/2017/02/18/description

A.J. Maguire http://ajmaguire.wordpress.com/

Rachael Kosinski http://rachaelkosinski.weebly.com/

Diane Bator http://dbator.blogspot.ca/

Rhobin Courtright http://www.rhobinleecourtright.com